After practicing viola for a few hours the other day, my right index finger was getting sore so I wrapped it up in a small cloth. This happens occasionally, always when I'm literally digging into soloistic material and using a particular viola bow that has a faux whalebone winding. It feels harder under the finger than the metal windings of my violin bows. I never have such issues with them. With a bit of a buffer between my finger and the winding I could continue practicing, but when it came time to mark a shift in my sheet music, to avoid upsetting my right hand situation, I tried using my left hand and couldn't help but laugh at how hard it was to write a legible "3" - with the same hand that had just felt so dexterous playing concerto and sonata passages!

I'm right handed, as you probably guessed, but I think this experience is worth mentioning as we explore the topic of whether left handed people should learn the usual way, or the opposite. Whatever way we decide to learn, the fact remains that playing violin family instruments require highly nuanced skills that everyone will need to develop on both sides. With that in mind, let's consider the benefits and drawbacks of learning to play violin, viola, or cello the opposite way.

Left Handed Instrument Selection: Unfortunately, setting up a left handed violin is much more complicated then simply reversing the strings - it needs to be the complete mirror image of a standard violin, meaning the strings, tailpiece, pegs, bridge, chin and shoulder rests if we use them, and internally, the bass bar and soundpost, all have to be flipped or fashioned the opposite way.

The main drawback to learning on a left handed instrument is that there aren't many left handed violins, violas, or cellos out there (or choices of accessories like chin and shoulder rests for that matter). While there are more being made in recent years due to higher demand, selection is still incredibly limited, especially beyond some basic student instruments. While a right handed player will be able to waltz into any shop and have the opportunity to try hundreds if not thousands of violins at every price point, a left handed player will be stuck with a few cheap models or having an instrument made from scratch, with most luthier's pricing starting around $15K, and often more like $25K for a custom instrument.

My partner, Canadian singer-songwriter Dan Frechette, is a left handed multi-instrumentalist on guitar and a number of other fretted stringed instruments (that's him in the photo above, trying to teach himself to fiddle many years ago). Though there are many more options for lefties among the types of instruments he plays, he’s struggled to find good instruments and longs for the quality and wide ranging options right handed people take for granted. He laments that the left-handed market is primarily online, through individuals and dealers. Most music shops might only have one or two left handed guitars in the corner, usually very basic instruments. He lives in a "buy before you try" world and he's had to literally buy and sell hundreds of instruments to find ones that meet his needs. He's had a few instruments custom made over the years, but generally prefers the sound of used, vintage instruments over new ones. These "holy grails" are very difficult to find. Other times, he's had right handed instruments converted. This is typically easier on plucked and fretted instruments then on a violin, as long as the internal bracing of the instrument is symmetrical - then it's only the saddle, nut, and strings that need to be changed. The pick-guard can be changed as well, but he's often just added a second pick-guard on the opposite side.

At one point Dan had to teach himself to play upside down (using a right handed guitar but the way he normally plays). Columbia Records had flown him to Los Angeles to record some demos of his songs and he didn't want to bring his guitar on the plane and risk damage. The folks at Columbia said they would rent him a nice left handed instrument for the session, but when he arrived, all they'd been able to secure was a nice right handed guitar. Between nursing a bout of food poisoning, he spent the two full days leading up to the recording session training himself to play his songs with his hands covering their typically duties, but all the chords and licks reversed on the fretboard. He pulled it off for the most part, but the deal fell through in the end. At least now he has a fun party trick and can grab a gorgeous $50K pre-war Martin off the wall of a shop and play something on it. But as far as gear he'd actually buy and perform on, he's still stuck with limited options. Dan’s proud to be a lefty, but has said that he’d probably save the headache and learn right handed if he had to do it over.

Ease of Learning: Learning to play a violin, viola, or cello requires time and dedication no matter what our dominant hand is and which way we decide to learn. For Dan, he started with air guitar on a tennis racket, held like a lefty. From there he graduated to a right handed guitar, but he always wanted to flip it over. One day his dad finally just strung it opposite. Dan remembers feeling like his left hand was his rhythm machine and there was no way to change that natural inclination to strum, pluck, and feel the beat there.

Played in the standard way, with the violin on the left shoulder and the bow in the right hand, some might think the setup is perfect for lefties. The left hand is poised to fly around the fingerboard with its heightened sensitivity to home in on all the right pitches. Considering all my left handed students over the years who have learned to play the standard way, I do think they sometimes have had an easier time developing their left hand technique.

However, the bow never gets enough credit. While the left hand prepares the note, it's the right that actually plays it - with its particular flavor of tone, articulation, dynamics, and color. Comparatively, the left hand duties with a standard violin setup are more mechanical and not particularly artistic. Either we're in tune over there, or we're not. In contrast, the right hand needs to be sensitive to weight, pressure, and speed, and has to execute refined motor skills, millisecond by millisecond. In this way, right handed people may actually have the advantage. Still, I've had many right handed students who've needed to work hard on their bowing, most of them in fact. Bowing is so rarely given the focus it needs and deserves.

Performance Opportunities: If the left handed student in question is a child, I think we also need to weigh the options carefully and avoid scenarios that might limit the child's future opportunities. When the student is an adult, and one wanting to learn for his/her own personal enjoyment, the choice can be a bit more personal.

One concern is if the left handed player ever wants to join an orchestra or ensemble. While not unheard of, groups taking on lefties will need to consider seating arrangements - bows going in the opposite direction can poke people in the face if there isn't ample room. When performing as a soloist, a violinist or violist will also need to stand on the opposite side of the stage in order to position the F-holes in the direction of the audience. While these are not insurmountable issues, they do require consideration and many groups and organizations unfortunately may not be open to adjusting.

Prior to performing with Dan I always sat or stood on the right side of the stage (from my perspective when looking out at the audience). It's where the first and second violins traditionally sit in a symphony or string quartet, and where a solo violinist stands due to how our instruments produce and amplify sound as mentioned above. However, playing with a left handed guitarist I've needed to switch to standing to his left to avoid crashing scrolls and head-stocks. The other option would be to stand several feet away from him, but especially in a duo configuration I think it looks a little silly and detached to have players standing far apart, not to mention the difficulty of hearing acoustic instruments clearly.

However, this means that in order to point my F-holes towards the audience I have to turn to the left, looking away from Dan when I need to project. Thankfully, we are both quite musically intuitive and can generally predict each other's timing without the need for visual cues, but I think it might add an additional dimension of engagement for our audiences and ourselves if we were to be able to visually connect with each other more.

Lesson Opportunities: It's nearly impossible to get to more advanced levels on a violin family instrument without a teacher. Since left handed players are rare, it may also be more difficult to find a teacher willing to teach a lefty. I've only taught two in my nearly 30 years of teaching, and both noted the difficulty they'd had finding someone who was willing to give it a try. In my experience as a teacher, it felt like my brain was being completely rewired during the first few lessons with these students. Everything was the same, yet completely the opposite! While I personally enjoyed the challenge (the Violin Geek Blog and Podcast were named for a reason after all!), I can imagine a lot of teachers not wanting to take on that challenge.

Given the potential drawbacks to learning violin, viola, or cello left handed in a world that unfortunately is setup for right handed people, I personally think we should all learn the standard way unless we have very good reasons to learn left handed.

In Dan's case, he may have been able to reach a professional level as a right handed player, but the pull to play the other way was very strong for him. As I mentioned, I have also taught a couple of left handed violin students over the years. Both were adults with very individual situations. One was already quite advanced on left handed mandolin and guitar and had been trying to teach himself to fiddle. His right hand was quite capable of finding the notes and playing melodies, so it made no sense to switch him around to playing violin the standard way. He already had a lot of skill he could carry over from his other instruments so we mostly just needed to teach his left hand/arm how to bow and produce a good tone. The other student had been born with a severe left hand deformity, so the only option for her was to have her right hand do the fingering while we fashioned a personalized bow hold with what she had on the left.

There are a few lefty violinists who've made names for themselves. The most famous currently may be Canada's Ashley MacIsaac, a Juno award winning fiddler/crossover artist from Cape Breton. Here's one of the many examples of his left handed playing:

Charlie Chaplin, while not famous as a violinist, also played left handed. Here he is playing in The Vagabond:

German virtuoso violinist Richard Barth also played left handed. After studying with Joseph Joachim through his teen years, he enjoyed a career as a soloist, concertmaster, conductor, teacher, and composer. While it's performed here by Jennifer Koh, Barth's Ciacona in B minor, Op.21 was composed as a post-Paganini tribute to J. S. Bach's Chaconne. An impressive blend of emotion, beauty, and technical difficulty, Barth left handedness clearly did not hold him back from expressing himself and his ideas.

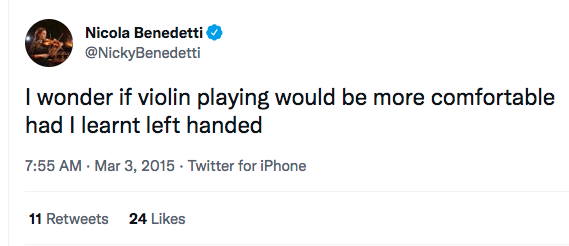

Finally, while she plays the standard way, Scottish violin soloist Nicola Benedetti, reportedly struggled to play right handed in the beginning and has mused about whether she would have had an easier time playing left handed:

As one of the most beloved players of her generation, she proves that no matter which side is dominant, with dedication and the right opportunities and support, it's possible to reach the top.

Happy Practicing!