When we first start playing, key signatures, those "hashtag," "pound sign," or baby "b" looking symbols to the right of the clef sign in our sheet music, might seem intimidating or even antiquated. After all, we probably have a teacher telling us where to place our fingers. However, without a teacher showing us the way, these symbols give us everything we need to know about where we can and cannot place our fingers during a piece or tune.

For example, in a key with three sharps, which would use the scale of either A major or F# minor, we need to place any F, C, or G notes in their sharp position, while all the rest (A, B, D, E) need to be in their natural position.

The only thing that can override the key signature is an accidental - a sharp, flat, or natural sign found immediately before a note somewhere within the music. However, accidentals are only valid from the note they appear on through the end of the measure, including any of the same pitches found in a different octave. (For example, a sharp on a G note found on the E string would also affect the open G string and mean that it would need to be played sharp rather than open as well.) But cross the bar line and we revert back to what the key signature tells us, until it changes or another accidental pops up.

While we could sit there deciphering each sharp or flat in a key signature each time we start learning a new piece or tune, committing at least the common ones to memory and being able to instantly interpret what finger patterns we'll be allowed, saves a lot of time and the potential of learning a piece incorrectly. There is never going to be one piece with three sharps that are (as they should be) F, C, and G, while another piece has three sharps too but this time they are B, C, and D, so it really doesn't make sense to have to get out the magnifying glass and inspect each one every time. Every key signature with three sharps will always have F, C, and G as those sharps and your finger patterns are always going to relate back to either the A major or F# minor scale.

Key signatures are universal, but violin family instruments are uniquely designed to help us learn them.

Explore the following tables:

| No sharps | 1 sharp | 2 sharps | 3 sharps | 4 sharps | 5 sharps | 6 sharps | 7 sharps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C major | G major | D major | A major | E major | B major | F# major | C# major |

| A minor | E minor | B minor | F# minor | C# minor | G# minor | D# minor | A# minor |

| No flats | 1 flat | 2 flat | 3 flat | 4 flat | 5 flat | 6 flat | 7 flat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C major | F major | Bb major | Eb major | Ab major | Db major | Gb major | Cb major |

| A minor | D minor | G minor | C minor | F minor | Bb minor | Eb minor | Ab minor |

If all that makes your head swim, don’t worry, the pattern isn’t as random as it looks. Everything fits together.

First off, we can usually tell whether we’re in major or minor after hearing the first phrase of a song. Does it sound happy, or at least not sad? Maybe stately or relaxed? Then the piece is most likely in a major key. Or maybe it does sound melancholy, or maybe mysterious, spooky, or angry? Anything moody is probably employing a minor key.

The notes a piece begins and ends on give us clues as well. If the melody begins and ends on a G and has one sharp in the key signature, then it’s most likely in the key of G. If instead it begins on a G but ends on an E, even if it still has just one sharp, we may need to weigh other clues.

Accidentals also give us clues about major versus minor. A piece containing many accidentals, particularly for the note that would be a half step/semi-tone under the “tonic” primary note of a minor key signature, usually indicates minor rather than major. For example, it's almost a sure sign that a piece is in G minor rather then Bb major if there are F# accidentals. Or for D minor rather then F major, there might be some C# accidentals.

Returning to our charts above, notice how moving between the relative major and minor, the minor key is always three notes down the scale from the major (including the starting and ending notes) otherwise known as a "minor 3rd" (depending on what's easier to imagine, either three half steps/semi-tones or a whole step plus a half step). For example, a G note steps down to an F# which steps down to an E = E is the relative minor of G major. Note that any sharps or flats in the key signature must be included - A major has three sharps (F, C, G), therefore stepping down from A to G# to F# to find the minor, it wouldn't be F minor, it would have to be F# minor.

Likewise, if you know the minor key, stepping up three notes within the scale, or a minor 3rd, will bring you to the relative major key signature. For example, B minor steps up to C# which steps up to D = D is the relative major of B minor.

Beyond this pattern found between the relative major and minor, all the key signatures add sharps or flats moving up or down the scale in perfect 5ths. Interestingly for violins, violas, and cellos, because our open strings are tuned in perfect 5ths we’re perfectly set up to find the key signatures in order of sharps or flats right off our fingerboards! For example, we can start with C major, which has no sharps or flats, and if we start stacking perfect fifths just like the viola or cello open strings: C - G - D - A - E etc. we'll find all the key signatures that progressively add sharps. To find our flats, we can start again with C, and go down the fingerboard in perfect fifths: C - F - Bb - Eb etc.

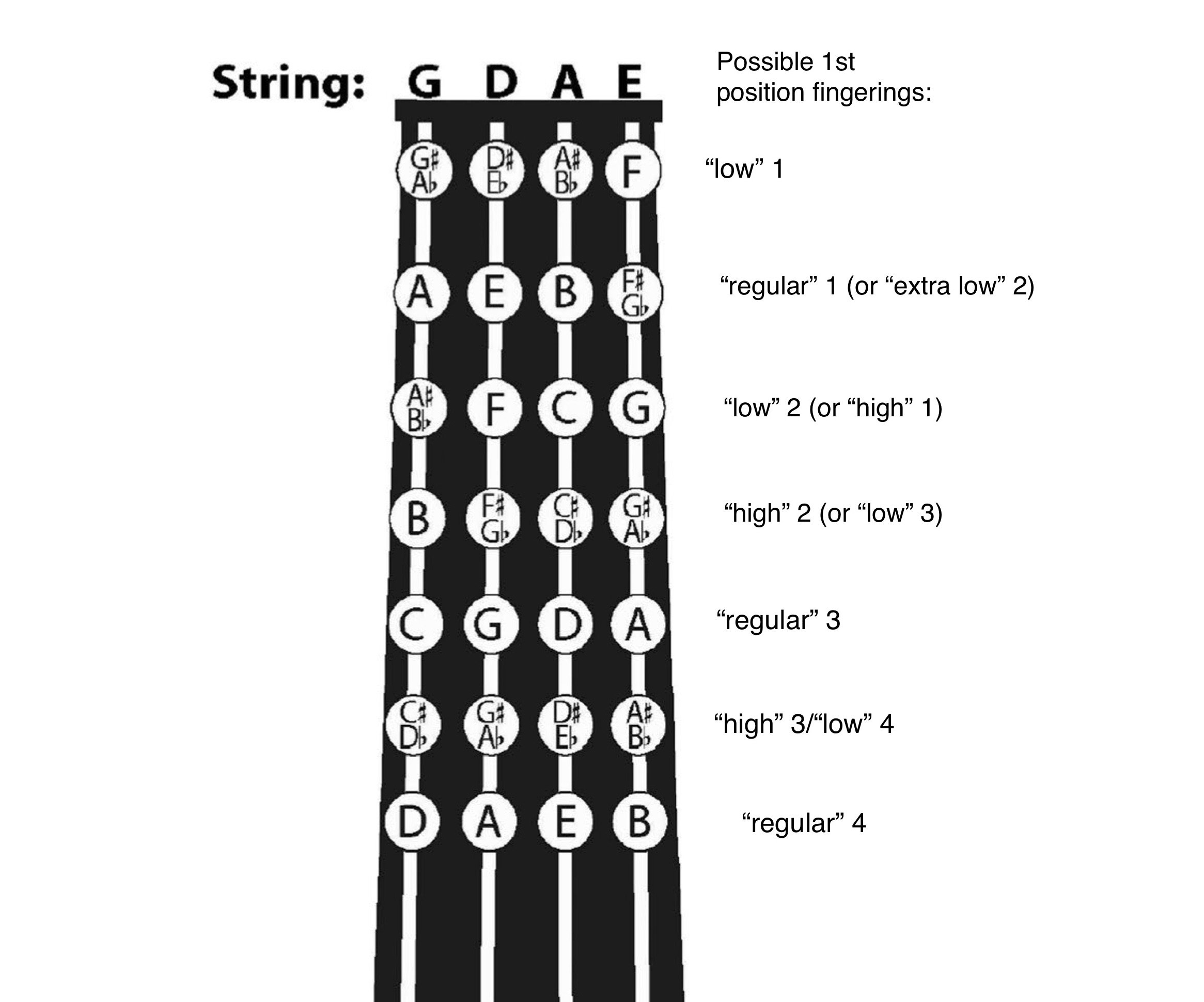

The following fingerboard chart names all our pitches in first position on the violin:

If we look at the pitches starting with "regular" third finger C on the G string, note how we can just hop that finger up a string and find G, then D, then A, just like the key signatures adding 1, 2, and 3 sharps respectively. Once we get to A on the E string we're out of strings, so we can start back on "regular" first finger A on the G string and we see that if we hop up a string from there we find E, then B, then F#, showing us the key signatures that add 4, 5, and 6 sharps respectively. Finally, we're out of strings again, but if we head back to "high" second finger F# on the D string and go up a string from there, we arrive at C#, our key with 7 sharps.

Whether we do major or minor, sharps or flats, we can always find the key that adds the next sharp up a string, either as the next open string or right across the fingerboard. For flats, whether major or minor, we'll always need to go down the strings (C hops down to F which hops to Bb etc.). This is what people mean when they talk about the “circle of fifths.” Eventually we circle around and get back to where we started.

Finally, it's helpful to know the pattern that exists within the sharps or flats of our key signature itself. For sharps, let's remember the saying "Fat Cats Go Down Alleyways Eating Bagels." The order of sharps, stacking across the staff from left to right, are F, C, G, D, A, E, B. For flats we can simply do the saying above in reverse, or we can remember this mnemonic: B-E-A-D Go Catch Fish. The order of flats, stacking across the staff from left to right, are B, E, A, D, G, C, F.

Finally, notice how even with the order of sharps and flats we are using the circle of fifths! Without the sayings above, we could return to our fingerboard and find our sharps if we start with our "low" second finger F on the D string and hop up a string to find C, then G etc. The same goes for the flats, but again, we have to go down a string from our starting point.

Armed with all this knowledge, it's possible to determine any key signature as long as you remember that C major and A minor have no sharps or flats.

While it's still helpful to memorize the key signatures and be able to recognize them at a glance, knowing these patterns exist helps create a framework around the memorization and a way to find the answer when you see a less common signature pop up, like one with 7 flats!

Happy practicing!